Emi Kanazawa

“Nihonga (日本画)” literally means “Japanese painting”.

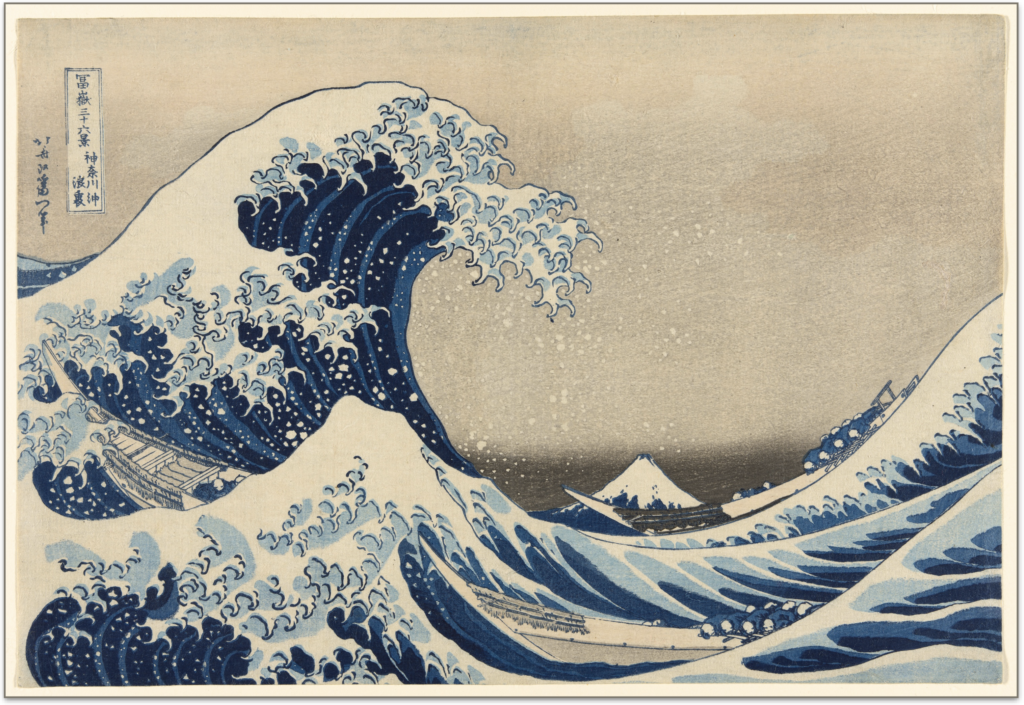

For most people, Japanese art will evoke an image of a simple outline of surging great blue wave from the left, by Hokusai. (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, The Great Wave off Kanagawa)

But this work by Hokusai is known as “Ukiyo-e (浮世絵)”, a separate genre and slightly different from Nihonga.

So, what actually is “Nihonga”?

目次

ESTABLISHMENT OF NIHONGA

History of Painting in Japan

The roots of Nihonga was in Chinese painting.

At that time, China was a great advanced country and there were already diplomatic exchanges between Japan and China. From around AD 600, regular dispatches of envoys, students of study, were sent from Japan to learn from the Chinese, their culture, Buddhism, social system and also the arts and craft.

Different era have its own interpretations, but approximately from AD 700 (Nara – Heian period) Chinese paintings and Buddhism painting from China (唐; Tang Dynasty in China, but known as “Kara” in Japan), as well as even those painted by Japanese using such learned skills, motifs and materials were collectively known as “Kara-e (唐絵)”.

However by around AD 900, the collapse of Tang dynasty saw a decline in Chinese influence. By then, Japan’s indigenous culture was already budding. Paintings with uniquely Japanese motifs, colours, compositions evolved. These were called “Yamato-e (大和絵)” and gradually differentiated from “Kara-e”.

Then from Heian period (794-1185) to around AD 1400, there were a separation in treating the paintings based on their themes; “Yamato-e” for Japanese themes and “Kara-e” for Chinese themes. From AD 1400 onwards, there were increasingly differences in styles. Hence, paintings utilizing Japanese indigenous style, materials and techniques were known as “Yamato-e”, whereas those using Chinese techniques or imported Chinese paintings were called “Kara-e”.

At that point in time, there was only a distinction made, in Japan, to present paintings of China as “Kara (唐 / eng: Tang)” or “Kan (漢 / eng: Han)” and that of Japan as “Yamato (大和)” or “Wa (和)” (ancient name for Japan). Beyond that, there was still no knowledge of the existence of other faraway foreign cultures and their totally different styles.

FACTIONS / SCHOOLS (STYLE)

Muromachi period (1336-1573) saw a greater difference from Kara-e and the blossoming of Yamato-e gave birth to many factions and schools of art/style.

These factions, each with their own art form, were patronised by the then powerful Daimyos (lords) or temples. The ateliers (with aspects of art schools) held by these factions; were groups of professional painters each holding numerous apprentices/disciples under their tutelage, made use of division of labour, to create great works. Among these, Kano school/faction (狩野派) (mid 1400-), Maruyama-Shijo school/faction (円山-四条派) (ca.1700-) or Rimpa school/style (琳派) (mid 1500-) were very influential for a long period of time.

These factions were very similar to that of medieval Europe where royalty, nobles keeping artists, or artists with ateliers and apprentices having the rich as their patrons.

At that time, photography was nonexistent, the rich commissioned portraits as a display of power, status and wealth; or the decoration of their residences. There were also paintings of religious and mythological themes to tell stories to the illiterates. Likewise, this need was also the same in Japan.

Birth of Nihonga

By mid 1800, after a long period of closed door policy, with minimal trading allowed for a few countries, Japan finally opened her doors. This saw the introduction of oil painting, a form of western art. The painting techniques, materials and style were totally alien to the Japanese. As such, oil painting became to be known as “Western painting (Japanese: 西洋画 / Seiyou-ga)” and emergence of such painters. This created a need to separate the indigenously developed style of “Yamato-e” and the oil painting of western techniques. Hence the concept of “Nihonga” was born.

Changes in Nihonga style

The opening of Japan saw the end of feudalistic government of the “Bakufu” and gave rise to a new constitutional system. Consequently the factions, schools lost their rich and powerful patrons.

Further, back in the early 1800’s “daguerreotype” a silver plated copper photography method was already established in France. The accurate record and reproduction by this, gradually changed the necessity of realistic paintings. Similarly, Japan with the influx of photography was also affected.

Because the need for such artisans was made redundant, it lead to the breakdown of factions. At the same time, mutual influence of art forms by different factions and western art had a great impact. Slowly the concept of faction, schools were eroded and led to a blossoming of individualistic expressions and free art styles in Nihonga.

DIFFERENCE OF STYLES

Till now, how Nihonga came about was introduced, but really, how does one differentiate western painting? The greatest difference is in the materials used.

Painting Materials

In the first place, paints were made from natural earth or minerals (synthetic pigments are also now chemically produced) mixed with glue. The powdery pigments cannot stay onto the painting surface by itself, for this, a fixative is required. Respective areas have their different earth and mineral. But it is the use of the fixative/binder that gives it its property.

Well known paintings (ca.1400-) in general used pigments mixed in drying oil. If it is mixed in resin, it will be known as acrylic painting. Such paints will produce a glossy finish.

On the other hand, Nihonga use “Nikawa (膠)”, an animal based collagen as a binder, which makes it water based. The finish will be like that of water colour, without gloss, somewhat like tempera painting which use egg as a binding medium, in medieval Europe (around 400-1400)

STYLE

There were also differences in styles. Western painting use light and shadow to create perspective, whereas on the other hand, traditional Nihonga specialised in capturing the shape itself. Using outline to produce flat and simple expression and also daring use of blank space. Classical themes such as landscape “Sansui-ga (山水画)”, flora and birds “Kacho-ga (花鳥画)”, beauty paintings “Bijin-ga (美人画)” all have their own styles.

Though Nihonga paints are water soluble, it does not dissolve easily. Because of this characteristic aspect, colours can be thinly layered, so the is no need for thick layering. As such it is also suitable to mix colours direct on the picture rather then mixing them on a palette. Compared to oil painting, gradation is not smooth therefore it is conceivable that in Nihonga, “line” is the core with its simple flat plane technique.

Besides the aforementioned colour paintings, there is also another genre known as “Suiboku-ga (水墨画 / eng: ink painting)”. Painting of ink and water as the name implies. Using shades of Sumi (墨 / eng: Ink) into a painting, is a typical Asian art form.

日本画 (Nihon-Ga) / Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, colour, and gold leaf on paper

JAPANESE ART AND WESTERN ART

At the same time, when the concept of Nihonga was conceived as earlier mentioned, Japanese art was also introduced to the West. Among these were Nihonga, crafts and also included numerous “Ukiyo-e”.

WHAT IS UKIYOE

There are two types; woodblock print Ukiyo-e called “Nishiki-e (錦絵)” and hand painted known as “Nikuhitsuga (肉筆画)”. Ukiyo-e; originating from Yamato-e, flourished from Edo period (1603-1868) to Meiji period (1868-1912), depicting the livelihood, manners and customs, and fashion of the ordinary people. Hokusai’s picture of the great wave mentioned in the beginning falls into this genre.

Recognised internationally as Japanese art, most of the renown works are of the colour woodblock prints called “Nishiki-e (brocade print)”. At that time, colour woodblock printing was exceptionally rare in the world, but in Japan, there was already an early establishment of artwork division, cheap reproduction made mass production possible. This quickly circulated amongst the common people as mass entertainment.

There is also Ukiyo-e that is directly painted with brush and paints called “Nikuhitsuga” (hand drawn painting). Being an only piece, it was treated more valuable than Nishiki-e which could be easily mass produced. However, Ukiyoe’s genre painting is different from Nihonga which is based on the classical style. Ukiyo-e is regarded as more in line with present day illustration.

Interactions

Nihonga, Ukiyo-e, with their unique forms of bold asymmetry, abstract composition without perspective and vanishing point was a great impact on the symmetrical and realistic executions of expressions of western painting. This popular trend in western art world became known as “Japonisme”. Impressionist and Post impressionist were inspired by the totally new composition, and by discarding perspective, were able to create new styles. And this change in western art was then brought back into Japan which influenced the Japanese art world including Nihonga with more varied forms of styles. Thus such mutual interactions of Western and Asian influence herald in changes to a new era.

西洋画・油彩画 (Oil painting) / Oil on canvas

Though the genre Nihonga was born out of circumstantial necessity and steadily evolving from its establishment, up to now, it is difficult to make its classifications in art. Even now, with increasing influence from within and outside the country, and also with traditional techniques, aesthetics, styles changing with the time, it becomes increasingly more difficult to define then before.

Hence, from the beginning to the present, the only thing that can ascertain the difference; is in the materials used. Simply put – traditional Japanese art materials or the use of Nikawa (animal based collagen glue) for paints are termed Nihonga. Beyond that, among intellects, there is such a blurring of delineation that till the present, the debate is still ongoing.

CONTEMPORARY NIHONGA

Nihonga in Japan still has a great presence. Like oil painting, printmaking and acrylic painting, Nihonga is firmly established as an equally important form of technique. There are many art universities offering separate painting courses for Nihonga or western art. However, as a high level of sketching skill is desired for Nihonga course examination, this is a formidable barrier for entry into Nihonga, as compared to other courses.

Also, the painting circle of Nihonga at present is very particular. To preserve and protect traditions there is an insular aspect in this world. There are many competitions for Nihonga. But to win and be famous; without master/disciple relation with a teacher/professor from a well-known art university and affiliated associations, one faces a tough barrier to this art stage. To be recognised as an independent is indeed very difficult in the current present.

Of course, in modern West, it too has its mentor and student relationship. One cannot deny the influence of the presence or non-presence of such mentors. However, opportunities for exposure and success for such independent individual artists are accessible. This is can also be said for the other fields of fine art in Japan. But in comparison, in the world of Nihonga the independent artist is left in a difficult and harsh position. It is undeniable that the insular Nihonga group, to protect and preserve traditions, set a high threshold and added value to maintain it.

Even though having such insularity aspect, it does not refuse what may come. For example, though Nihonga’s roots were from Chinese paintings, China has lost a lot of these skills. To revive and reinvigorate, artists came to learn Nihonga, and to them, the doors were opened. However, to find success in the Nihonga world one have to join a group which is makes it very exclusive.

MATERIALS USED IN NIHONGA

Lastly, these are the principal materials that are essential to make Nihonga:

Support

Silk (絹: Kinu) — One of the important materials used in Nihonga. Painting on silk is known as “Kenpon (絹本)”. Paints and leaf/foil can be painted or applied to the back of fine and transparent silk. With silk, it is possible to create various expressions and also delicate gradation. Expensive.

Washi (和紙) — Like silk, Japanese paper “Washi” is an equally important material. Painting on Washi is called “Shihon (紙本)”. The difference between ordinary paper or western paper and Washi is the fluffy edges formed when tearing it. A popular material because of its durability, easy to handle and wide price range. There are many varieties with their own features. As such, Washi has been used for cultural restoration work in and outside Japan.

Painting Materials

Sumi (墨)/ Inkstick — Made from lampblack/soot kneaded with Nikawa and dried. To use, add water and grind on a “Suzuri (硯 / eng: Inkstone)”.

Nikawa (膠) — Gelatine extracted from the boiled proteins of animals, fish skin, and bones. Used since antiquity as a glue. When using Nikawa, environmental factors will greatly affect the quality and condition of the product. Adjustments must be done for different grain sizes. If too much Nikawa is added, the paint will crack easily, if too little, it will peel off easily.

Mineral paint (岩絵具: Iwa-enogu) — Pigment. Natural minerals pulverised finely are known as mineral paints. Shades are obtained by using different grain sizes. It can be roasted to change its colour. Nikawa is used as a binder.

Soil/Clay paint (土/泥絵具: Tsuchi/Doro-enogu) — Pigment. Ordinary soil or clay dissolved in water and dried. Used as yellow or vermillion. Artificially dyed pigments are also manufactured. Nikawa is used as a binder. Another name: Suihi-enogu (水干絵具).

Gofun (胡粉) — Pigments made from original whites of oyster shells. In the early stage, Gofun from white lead was imported from China. But from around 14th century onwards, Gofun made from oysters became the norm. Nikawa is used as a binder.

Dyestuff (染料: Senryo) — Colours abstracted from flora and fauna. Natural dye. If unable to use it in original state, adsorption by Gofun or lime to make paints.

Haku (箔) / Dei (泥) — Metals hammered thinly into foils are called leaf “Haku”. There are gold leaf, silver leaf, platinum leaf and others. Nikawa is used to glue the leaf onto the painting. There are also techniques for scattering stringlike strips and coarse grains. Leaf made into powder form is known as “Dei”. Similarly, like leaf, there are gold-dei (金泥: Kin-dei), silver-dei (銀泥: Gin-dei) etc. Nikawa is used as a binder.

Temperature, humidity and other factors will affect the condition of the raw materials. Moreover, mixing during under-paint or during the finish must be meticulously compounded. This makes it very difficult to handle and requires years of learning and practice of such skills. As such, Japan having a long tradition of such apprenticeship, techniques of Nihonga seems to be suitable to the Japanese temperament.

Some years back, it was almost very difficult to obtain materials for Nihonga. However, lately there is an increasing number of art-shops handling such materials. For those interested, please pop-in and browse through and take a look at what Nihonga materials are, in one of these shops. It would be a great pleasure if one can experience a greater affinity with Nihonga.